Key points

- Insufficient data are available on actual rates of collection adherence in opiate users treated with controlled drugs dispensed on an FP10MDA instalment prescription form.

- There are overall high levels of collection adherence in this group.

- Poor collection adherence is associated with other risk markers, including injecting non-prescribed drugs, use of illicit opiates and adjunctive stimulant use.

- Associations between poor adherence and receipt of supervised consumption and methadone treatment may be driven by relationships between measured markers of complexity (e.g. adjunctive alcohol use and use of ‘on-top’ opiates).

- Interventions targeted at opiate users with risk of poor adherence are required.

Introduction

Opioid use disorder is defined by the American Psychiatric Association as “a problematic pattern of opioid use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress”[1]

. The use of opioid-agonist medicines, such as methadone or buprenorphine, is conventionally referred to as medication-assisted treatment (MAT) and is recommended in this patient group[2]

. Both methadone and buprenorphine have evidence supporting their clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, and the decision about which to prescribe should be made in consultation with the service user[3]

.

Adherence with the prescribed MAT regimen has been identified as a crucial part of achieving successful treatment outcomes and the prescriber must be satisfied that the patient is able to comply with the prescribing regimen during their period of treatment[2]

. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends that “methadone and buprenorphine should be administered daily, under supervision, for at least the first three months” and that “supervision should be relaxed only when the patient’s adherence is assured”[3]

. The Department of Health’s 2017 clinical guidelines do not explicitly propose a recommended time period, instead advising that patients who are newly prescribed methadone or buprenorphine are required to take daily doses, “under the direct supervision of a professional for a period of time to allow monitoring of progress and an ongoing risk assessment”[2]

. Supervised consumption, however, may be associated with poor adherence, especially where weekend pharmacy dispensing is not available[4]

, leading to insufficient levels of support.

Adherence with scheduled pick-up of MAT is vital to prevent overdose. If an individual receiving MAT does not take their regular prescribed dose, their tolerance to the drug may reduce, increasing their risk of overdose if the usual dose of MAT is then subsequently taken[2]

.

Dispensing MAT, such as methadone and buprenorphine, on an FP10MDA instalment prescription form for controlled drugs, attracts a fee payable to the dispensing pharmacy. As well as the standard dispensing fee, payment is a fixed additional amount on each occasion the pharmacist provides an instalment to the patient (i.e. each time the patient collects their medicine from the pharmacy)[5]

,[6]

. However, insufficient data are currently available to establish actual rates of collection adherence in treated individuals.

This study aimed to determine the percentage of FP10MDA medication doses collected in accordance with the prescribed collection regimen among opiate users in English treatment services, as well as a statistical analysis of collection adherence (using available demographic, clinical and risk characteristics).

Methods

Sites

This study was a collaboration between the University of Manchester and Change Grow Live — one of the main UK third-sector providers of substance misuse treatment services. The study was conducted across five of the nine English geographical regions: Birmingham, East Lancashire, Hertfordshire, Stockton and West Kent. Sites were chosen for their geographical spread and to cover citywide and countywide treatment services. All five sites approached agreed to be involved. Each site included several pharmacies to which Change Grow Live referred patients for MAT.

Timescale

The study covered the 91-day period from 1 September 2017 to 30 November 2017.

Patient demographics

To be eligible for inclusion in the study, patients had to be aged 18 years or over, in receipt of treatment for opioid use disorder (prescribed formulations of methadone or buprenorphine) at a Change Grow Live treatment site. Patients in the sample had their MAT dispensed using an FP10MDA instalment prescription form for controlled drugs. To provide information on stabilised service users, at least three months had elapsed since the recovery assessment triage for participating individuals.

Sample size and data collection

The five sites included in this study comprised around 6,196 patients receiving MAT. A sample size of 5% was deemed appropriate to be indicative of the wider treatment population and feasible to obtain in the timescale available. Consequently, the aim was to conduct a cross-sectional survey of collection adherence among a randomly selected cohort (n=300) of service users whose MAT was dispensed using an FP10MDA instalment prescription form for controlled drugs. This initial cohort target was split equally between the five participating Change Grow Live sites (i.e. n=60 patients in each site).

The sample was randomly selected from the Change Grow Live case management system (CRiiS), using the Fisher–Yates algorithm; a simple shuffle method where each eligible individual has an equal chance of being picked first, second, third and so on. Participating pharmacies that dispensed MAT medicine for members of the study cohort were notified and informed of the procedure for returning data on collection adherence. Participating pharmacies received £30 remuneration per returned form, in which they were required to record actual collection patterns, in addition to the initials and date of birth of the patient, which enabled linkage with the CRiiS data system.

However, several participating pharmacies failed to supply data on members of the randomly selected cohort. Only 45 out of the 146 pharmacies returned data to the study. Therefore, the decision was taken to extend the cohort to include non-randomly selected service users in order to boost participation and reach the target sample size.

The decision was taken to examine a non-random group which included:

- Additional service users meeting the inclusion criteria, who were identified by the 45 participating pharmacies (inclusion of this group was suggested by participating pharmacies);

- Additional service users meeting the inclusion criteria, at participating sites, whose details were recorded on the CRiiS data system. The rationale for inclusion of this group was that data required by the study were available from existing secondary data sets as these patients were in receipt of supervised consumption.

Ethical approval

The survey was deemed to constitute a service delivery audit; ethical approval was, therefore, not required, as determined via Health Research Authority decision tools.

Data analysis

The collection adherence rate of the overall cohort and subgroups was established as a percentage. Median and interquartile range (IQR) data were reviewed in addition to mean data. Subgroups of adherence levels were defined to ease analysis (based on consultation with the associate medical director and nursing director) as:

- Optimal adherence (100%);

- Suboptimal adherence (90–99%);

- Inadequate adherence (75–89%: not enough to mitigate additional [on-top] use of illicit opiates);

- Unsatisfactory/poor adherence (≤74%: not engaging sufficiently with MAT).

Logistic regression analyses were informed by chi-square tests and t-tests. A descriptive analysis of the study cohort used demographic information (i.e. age, gender and ethnicity); available clinical characteristics (i.e. receipt of supervised consumption, the MAT taken, any dose change during the study period and the length of the current treatment episode); and available markers of risk (i.e. injecting status, use of on-top illicit opiates, adjunctive stimulant use [crack cocaine, powder cocaine or amphetamines] and alcohol use).

Data were sourced from information collected during the study itself (i.e. dose change), extracted from the CRiiS dataset (i.e. age, gender, ethnicity, supervised consumption, MAT taken and length of current treatment episode), or sourced via the most recent treatment outcomes profile (TOP) assessment (i.e. injecting status, on-top opiate use, stimulant use and alcohol use). TOP data are collected at regular intervals within UK substance use treatment (on average every 3–6 months) and comprise self-reported data covering the 28 days prior to the TOP assessment[7]

.

Results

Sample size

Insufficient data were available to identify 14% (n=27/194) of the sample, as a result of missing identifiers (i.e. ID codes, names, dates of birth) predominantly in the pharmacy-collected data. Therefore, these individuals were removed from the sample.

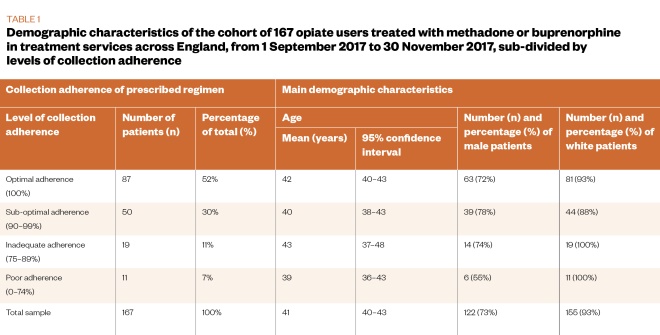

The final study sample comprised 167 service users, made up of a randomly selected group (n=108, 65%) and a non-randomly selected group (n=59, 35%). This final sample represented 56% of the target sample size for the study. The whole study sample was analysed together, following analysis to establish that the randomly selected group and the non-randomly selected group were statistically comparable on the measures assessed (see Table 1 and Table 2).

Patient demographics

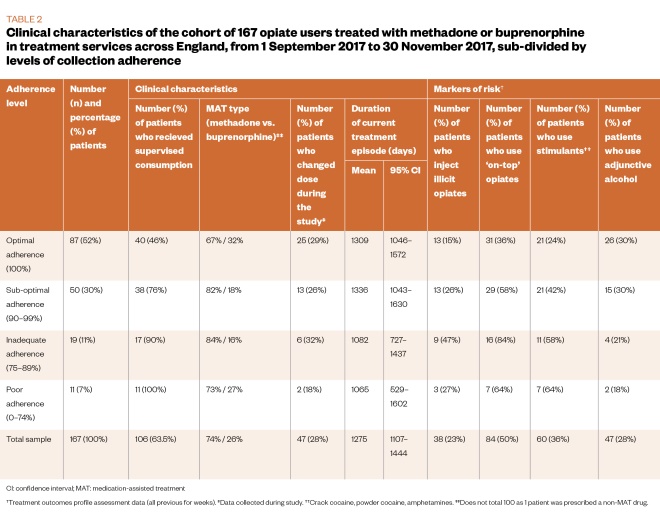

The main demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample are described in Table 1 and Table 2. The cohort (n=167) was mostly male (73%, n=122) and white (93%, n=155), with an average age of 41 years. The majority (74%, n=124) of the sample was treated with methadone and in receipt of supervised consumption (63.5%, n=106).

Regarding available markers of risk, 50% (n=84) of the sample reported on-top opiate use, 36% (n=60) reported adjunctive stimulant use, 28% (n=47) reported use of alcohol, and 23% (n=38) reported injecting non-prescribed drugs in the 28 days prior to their latest TOP assessment.

Findings

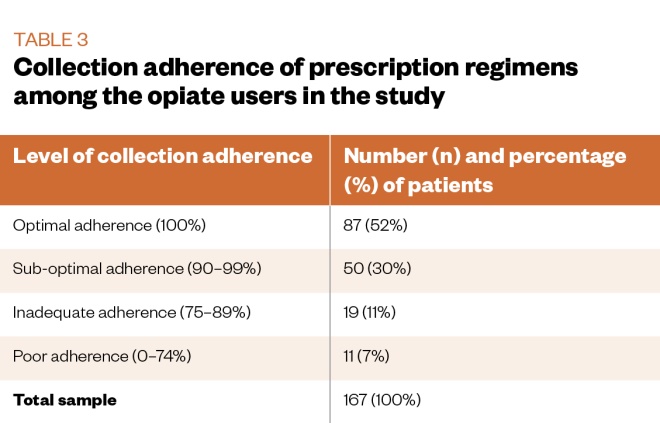

The mean collection adherence rate was 93.2% (95% confidence interval [CI] 90.8–95.5; median 100%; IQR 8). Table 3 describes the subgroups of adherence levels. A small majority (52%) of service users had optimal (100%) adherence rates throughout the three-month study period.

Associations between clinical characteristics and level of adherence were examined using a series of chi-square tests. Significant associations were found between adherence level and receipt of supervised consumption (chi-square=27.55; P <0.001); injecting status (chi-square=9.61; P=0.018); on-top opiate use (chi-square=18.46; P<0.001); and adjunctive stimulant use (chi-square=13.61; P=0.003). As shown in Table 2, there was a lower proportion of participants in receipt of supervised consumption, people who inject illicit drugs, on-top opiate users or adjunctive stimulant users in the higher adherence level category.

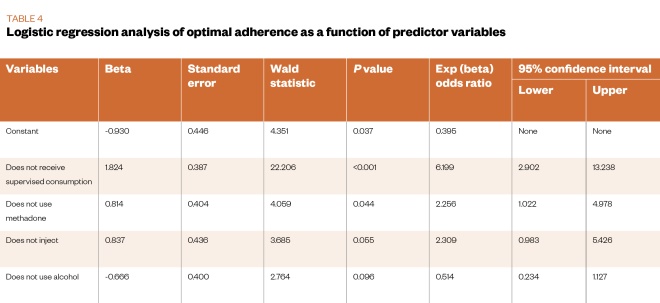

In order to examine predictors of adherence, the sub-optimal, inadequate and poor adherence groups were combined into a single group. A binary logistic regression analysis was used to predict the likelihood of being in the optimal (100%) adherence group, using the simplest model. Variables included in the model were the demographic and clinical characteristics, and the markers of risk presented in Table 1 and Table 2. The final model identified four predictors as reliably distinguishing between service users with optimal adherence and those who were not (chi-square=35.25; P<0.001). The proportion of variance accounted for by the model was between 19% and 26%, with 70% of service users in the optimal adherence group correctly predicted. The overall success rate of the model was 69%.

Table 4 shows the main statistics for the binary logistic regression analysis. Service users in the optimal adherence group were less likely to be in receipt of supervised consumption; more likely to be treated with buprenorphine; less likely to inject illicit drugs; and more likely to use adjunctive alcohol.

According to the Wald test, two of these four predictors in the final model reliably predicted optimal adherence levels (i.e. no supervised consumption of MAT and receiving buprenorphine treatment). The odds for service users not receiving supervised consumption of MAT demonstrating optimal adherence were 6.2 times higher (95% CI 2.9–13.2) than those for service users receiving supervised consumption. The odds of service users treated with buprenorphine demonstrating optimal adherence were 2.3 times higher (95% CI 1.0–5.0) than those for service users treated with methadone (see Table 4).

Supplementary analysis

Binary logistic regression was used to further examine two predictors of poor collection adherence — receipt of supervised consumption and methadone treatment. Service users receiving supervised consumption and/or treated with methadone may differ from other service users in terms of measured (and unmeasured) complexity, which may well result in poor adherence.

Logistic regression analysis reliably distinguished between service users treated with methadone and those who were not (chi-square=48.47; P <0.001) via the identification of three predictors: they were more likely to use adjunctive stimulants, they were more likely to use on-top opiates and they were more likely to have a longer treatment episode. The proportion of variance accounted for by this model was between 25% and 37%, with 86% of service users treated with methadone being correctly predicted.

A further three variables also predicted individuals in receipt of supervised consumption (chi-square=30.72; P<0.001). These service users were more likely to use adjunctive alcohol, more likely to use on-top opiates and less likely to have a longer treatment episode. The proportion of variance accounted for by this model was between 17% and 23%, with 88% of service users receiving supervised consumption being correctly predicted.

Discussion

The mean collection adherence rate was 93.2%. More than half (52%) of service users had optimal adherence rates throughout the study period. However, levels of adherence among the cohort varied according to several variables (i.e. supervised consumption, injecting status, on-top opiate use, adjunctive stimulant use, alcohol use and MAT type). Optimal adherence was associated with receiving buprenorphine treatment and not receiving supervised consumption.

Limitations

The original aim of the study was to examine a randomly selected cohort of eligible service users. In order to counter selection bias, data were collected on a subgroup of randomly selected participants who were identified via a computer-generated lottery using the Fisher–Yates algorithm. A clear limitation is that supplementing the study group with a non-randomly selected subgroup had the potential to introduce bias owing to systematic differences in the behaviour of the opiate users examined. This potential bias was countered by additional data analysis to establish the comparability of the randomly selected and non-randomly selected subgroups ahead of an examination of adherence rates and associations.

Ideally, the representativeness of the study sample would have been established via comparisons of the sample’s demographic and clinical characteristics with those of the overall Change Grow Live MAT population. This was not possible owing to time and resource constraints. This could be a further limitation, although the study sample was comparable to the national cohort of service users currently receiving treatment for opioid use disorder on gender (73% male vs. 73% male), ethnicity (93% white vs. 90% white) and age (median 41 years vs. median 39 years)[8]

.

Additional limitations include issues of missing data —with 14% of the obtained sample having insufficient data to match them with the CRiiS data system — and a small overall cohort sample size. Data not being returned by participating pharmacies, together with missing data, meant that the final study cohort represented 56% of the original target sample size for the study. Lower than expected rates of participation may have led to selection bias, meaning that these results may not be representative of the wider cohort of those with opioid use disorder in UK treatment services. Although the study had a wide geographical spread, it took place in just five Change Grow Live treatment sites in England.

Secondary findings

The main finding that optimal (100%) adherence was associated with receiving buprenorphine treatment and not receiving supervised consumption was supplemented by the provision of additional analyses.

The Department of Health’s 2017 clinical guidelines advise that new patients prescribed methadone or buprenorphine be required to take daily doses, “under the direct supervision of a professional for a period of time”[2]

. Usually, the person supervising consumption will be a community pharmacist. This requirement is reviewed on a regular basis while the patient is undergoing treatment, and takes into account individual need and risks both to the individual and others. As a result, service users receiving supervised consumption and/or treated with methadone may differ from other service users in terms of measured (and unmeasured) complexity. In terms of measured indicators of complexity analysed in this study, those in receipt of supervised consumption were more likely to use adjunctive alcohol and more likely to use on-top opiates. Service users treated with methadone were more likely to use adjunctive stimulants and were more likely to use illicit opiates on-top. A major goal of MAT is to provide the dose that leads to complete cessation of use of illicit opioids, although it is acknowledged that this can take a substantial period of time to achieve[2]

.

Clinical implications

Collaborative working between prescribers and community pharmacists is imperative in achieving successful outcomes for patients. Improving adherence through strong relationships between the patient and healthcare professionals can help to optimise medication treatment, reduce harm associated with diversion, and promote wider public health education. It is hoped that these findings will re-emphasise to community pharmacists the value of reassessing poor collection adherence as a marker of risk and as a predictor of other potential risks to the patient.

Individuals with poor collection adherence have other markers of risk, such as injecting status, on-top opiate use and adjunctive stimulant use. Poor adherence is also associated with receipt of supervised consumption and treatment with methadone. It is possible, however, that these associations are driven by the relationships between those markers of complexity and supervised consumption or methadone treatment. It is also possible that there are additional unmeasured indicators of risk and complexity that may differentiate between individuals with optimal adherence and poor adherence, between individuals in receipt of supervised consumption and those who are not, or between those individuals treated with methadone and those treated with buprenorphine. It is, therefore, important to note that the study design does not permit inferences around causality; it may be that service users compliant with MAT collection were assigned to non-supervised consumption and/or buprenorphine owing to their adherence, rather than vice versa.

Formal, routine measurement of client complexity using a valid tool, such as the addiction dimensions for assessment and personalised treatment (ADAPT)[9]

, or similar, would be of value to future similar research. The ADAPT tool provides summary measures of severity and complexity and would allow for a formal examination of whether service users are assigned to different MAT based on currently unmeasured complexity.

It is important to emphasise the caveats surrounding the observed relationships between poor collection adherence and other risk markers, which result from the study limitations set out previously. Interventions to improve adherence, targeted specifically at opiate users with a higher risk of poor collection adherence, could improve patient care and are, therefore, worth investigating. This would facilitate MAT optimisation while also minimising potential harms to service users. One such intervention, contingency management, has already demonstrated beneficial effects on adherence among substance users, specifically adherence with naltrexone treatment[10]

. Contingency management involves the reward, or reinforcement, of positive behavioural change, often via the use of monetary-based incentives, such as shopping vouchers[11]

. Although it is recommended by NICE[12]

and there is evidence of its efficacy in real-world settings, contingency management remains underused in the management of opioid use disorder in the UK[13]

. Long-acting buprenorphine preparations could also improve adherence in this group via consistent treatment exposure[14]

. Such preparations have demonstrated a beneficial impact on the on-top use of illicit opiates in clinical trial settings and appear likely to be incorporated into routine service delivery[15]

.

Conclusion

Poor collection adherence of methadone or buprenorphine among opiate users is associated with other markers of measured complexity and may be associated with unmeasured indicators of risk and complexity. Routine use of a valid measure of complexity would be of value to future research. Interventions to improve collection adherence, targeted specifically at opiate users with a high risk of poor adherence, are required and have the potential to improve outcomes in this patient group.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank those individuals who made the study possible — specifically Jeff Crouch, data manager at Change Grow Live, and the pharmacists based at participating pharmacies. Data analysis advice was supplied by Andrew Jones, senior lecturer at the University of Manchester. The study was also supported by Caroline Grundy medicines management pharmacist at Change Grow Live).

Financial and conflicts of interest disclosure

This study was funded via an unrestricted educational grant from Indivior, a pharmaceutical company that manufactures extended-release buprenorphine, and hosted by Change Grow Live, one of the main UK providers of substance use disorder treatment services.

MF, the chief pharmacist at Change Grow Live, is lead author of this article, contributed to the inception and design of the study, and to the final writing of the paper.

The funder had no involvement in the design or undertaking of the study. No writing assistance was used in the production of this manuscript.

MF: Member of the UK Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD).

KH: Has received research grant funding from Change Grow Live, a third-sector provider of substance misuse services. She received no research funding or personal remuneration from the funder of this study.

PB: Member of the ACMD technical committee, executive member faculty of addiction psychiatrists at the Royal College of Psychiatrists.

HW: No conflicts of interest to report.

TM: Member of the ACMD and has received research funding from the National Treatment Agency for Substance Misuse/Public Health England, the Home Office, the Department of Health, and Change Grow Live. He has chaired and organised conferences supported by unrestricted educational grants from the pharmaceutical industry (no personal remuneration). He has received speaker honoraria from an independent healthcare consultancy. He received no research funding or personal remuneration from the funder of this study.

References

[1] American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th Edn. Philadelphia: APA; 2013

[2] Department of Health. Drug misuse and dependence: UK guidelines on clinical management. 2017. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/drug-misuse-and-dependence-uk-guidelines-on-clinical-management (accessed October 2019)

[3] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Methadone and buprenorphine for the management of opioid dependence. Technology appraisal guidance [TA114]. 2007. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta114 (accessed October 2019)

[4] Haskew M, Wolff K, Dunn J & Bearn J. Patterns of adherence to oral methadone: implications for prescribers. J Subst Abuse Treat 2008;35(2):109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.08.013

[5] Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee. Methadone dispensing (FP10 and FP10MDA). 2013. Available at: https://psnc.org.uk/dispensing-supply/dispensing-controlled-drugs/methadone-dispensing (accessed October 2019)

[6] Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee. Instalment dispensing. 2016. Available at: https://psnc.org.uk/dispensing-supply/dispensing-controlled-drugs/instalment-dispensing (accessed October 2019)

[7] Marsden J, Farrell M, Bradbury C et al. Development of the treatment outcomes profile. Addiction 2008;103:1450–1460. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02284.x

[8] Public Health England. Substance misuse treatment for adults: statistics 2016 to 2017. 2017. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/substance-misuse-and-treatment-in-adults-statistics-2016-to-2017 (accessed October 2019)

[9] Marsden J, Eastwood B, Ali R et al. Development of the Addiction Dimensions for Assessment and Personalised Treatment (ADAPT). Drug Alcohol Depend 2014;139:121–131. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.03.018

[10] Carroll KM, Ball SA, Nich C et al. Targeting behavioral therapies to enhance naltrexone treatment of opioid dependence: efficacy of contingency management and significant other involvement. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001;58(8):755–761. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.8.755

[11] Petry NM. Contingency management: what it is and why psychiatrists should want to use it. Psychiatrist 2011;35(5):161–163. doi: 10.1192/pb.bp.110.031831

[12] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Drug misuse in over 16s: psychosocial interventions. Clinical guideline [CG51]. 2007. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg51 (accessed October 2019)

[13] Prendergast M, Podus D, Finney J et al. Contingency management for treatment of substance use disorders: a meta-analysis. Addiction 2006;101(11):1546–1560. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01581.x

[14] Rosenthal RN & Goradia VV. Advances in the delivery of buprenorphine for opioid dependence. Drug Des Devel Ther 2017;11:2493–2505. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S72543

[15] Lofwall MR, Walsh SL, Nunes EVet al. Weekly and monthly subcutaneous buprenorphine depot formulations vs daily sublingual buprenorphine with naloxone for treatment of opioid use disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2018;178(6):764–773. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.1052

You may also be interested in

Drug-related deaths among people treated for opioid dependence more than treble in ten years, study finds

There is a vulnerable group we must not leave behind in our response to COVID-19: people who are dependent on illicit drugs