Key points:

- Community pharmacy is well positioned to offer a point-of-care (POC) C-reactive protein (CRP) test to reduce the burden of unnecessary presentation at GP surgeries with viral respiratory tract infections (RTIs).

- This study investigated the feasibility of a rural community pharmacy offering this service and delivering the most appropriate intervention in RTIs.

- In total, 52 patients entered the study. Overall, 25 patients were referred via the GP surgeries, 6 by pharmacy staff and 21 self-referred as a result of a local awareness campaign. Of this, 44 patients were suitable for POC CRP testing.

- Of the 44 patients who received a POC CRP test, 6 patients were referred to the GP surgery, 5 allocated to a ‘watch and wait’ category and 33 recommended self care. Of the ‘watch and wait’ and self-care patients, none revisited the pharmacy or their GP.

- Overall, 95% of patients receiving the test reported that they would have otherwise visited the GP and would have expected antibiotics.

Introduction

Respiratory tract infections (RTIs) are common and reports show that they account for around 60% of antibiotics issued within primary care[1]

. However, it is suggested that acute RTIs are often viral and self-limiting[1],[2],[3]

. A study of acute pharyngitis conducted in GP practices in England in 2014–2015 found that antibiotics were prescribed in 62% of cases, despite it usually being caused by viral infection[4]

. Furthermore, in a 2011 UK survey, 58% of participants reported having a respiratory infection in the previous six months and a fifth had contacted their GP, with 53% stating that they expected to receive antibiotics[5]

. Despite community pharmacy being well placed to help patients manage symptoms or signpost for further investigation, only 6% of patients asked a pharmacist for advice[6]

. Research conducted by the Wellcome Trust has shown that patients associate antibiotics with having ‘a real illness’ and ‘proof that they are ill’[7]

. This research also found evidence that patients research symptoms beforehand in order to obtain antibiotics[7]

.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends that point-of-care (POC) C-reactive protein (CRP) testing should be considered in adult patients presenting with symptoms of lower RTI in primary care where clinical assessment is inconclusive and it is unclear whether antibiotics should be prescribed[8]

. Additional recommendations regarding antibiotic use in these conditions have been issued by Public Health England and updated European guidelines are also relevant in this context[9],[10]

. A Cochrane systematic review concluded that POC CRP testing reduced antibiotic use in patients with acute respiratory infections, with no difference in the overall clinical recovery of patients[11]

. Studies of POC CRP testing in RTIs have also highlighted potential cost savings[11],[12],[13],[14],[15]

.

Community pharmacy is well positioned to offer a POC CRP test, whereby patients can be screened to reduce the burden of unnecessary presentation at GP surgeries with viral RTIs. As suggested by several authors, POC CRP tests can be performed rapidly and the appropriate course of action signposted, with an extensive range of self-care medication immediately available, should this be the preferred recommendation[16],[17],[18],[19]

.

This pilot study in North Staffordshire, UK, sought to investigate the feasibility of a rural community pharmacy delivering POC CRP testing to help evaluate the most appropriate intervention in RTIs and integrate this service with local GP surgeries. It also sought to assess patient enablement, satisfaction and future consulting intention, and the use of healthcare services, including reconsultation as well as antibiotic prescribing following the initial consultation.

Methods

Pharmacy selection

This was a prospective pilot study in one community pharmacy in a rural setting. The pharmacy was selected by North Staffordshire Local Pharmaceutical Committee (LPC) owing to the good relationship it has with the local GP practices and its location (it is easier for patients to access POC CRP testing here than at local hospital facilities).

Device selection

The device selected for the study was the Suresign Finecare II POC analyser and CRP test (CIGA Healthcare; UK). This test is based on a fluorescent immunoassay principle and consists of: a liquid for sample dilution and lysis of cells; and a test cassette with CRP-specific monoclonal antibodies coated to a membrane. A single drop of blood (8.5µl) from a finger prick is required to perform the test and results are available within three minutes. Guidance for CRP interpretation in RTIs can be seen in Table 1.

| Point-of-care CRP testing score | Meaning | Action to be taken |

|---|---|---|

| CRP >100mg/L | Bacterial infection | Refer to GP |

| CRP between 20mg/L and 100mg/L | Possible bacterial infection | Watch and wait |

| CRP <20mg/L | No bacterial infection | Reassure patient and recommend self care |

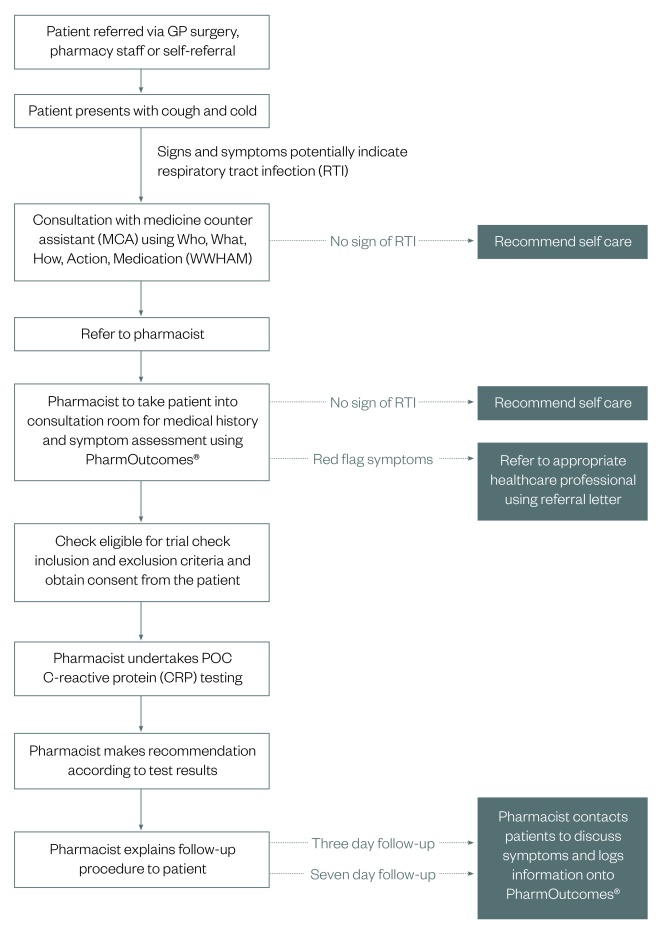

POC CRP scheme

A management pathway was developed by the authors, taking into consideration the NICE clinical guideline CG191 (see Figure 1). As a result of the protocol development, several documents were produced and provided to the community pharmacy to support the use of the POC analyser and CRP test in practice and presented to the pharmacy team during a training session. A qualified representative from the analyser supplier delivered the initial operator training and evaluated the subsequent competency assessments with the pharmacy team. Each day prior to use of the Finecare II analyser, a quality test cartridge supplied with the analyser kit was used to act as an internal validation of the analyser hardware. This ensures that all internal systems are working correctly, in particular, optical systems, transmission systems and electrical systems. Only a positive validation of all of these systems allows the analyser to be used. Every Finecare test cassette incorporates an on-board control to confirm the test has operated correctly and should this fail, the operator will be alerted and a result will not be provided for that particular test. A UK National External Quality Assessment Service (NEQAS) POC CRP scheme is also available for the Finecare CRP test. A standard operating procedure (SOP) was put in place for the service as outlined on the LPC website[20]

. Patients had access to an approved private consultation area. The service was available during pharmacy opening hours.

Figure 1: Management pathway for patients

Pathway for patients presenting with symptoms of lower respiratory tract infection (RTI) in primary care where clinical assessment is inconclusive

Relevant members of staff in the local GP surgeries were briefed about the service with clear guidance relating to signposting suitable patients to the community pharmacy. Posters advertising the service were displayed in the pharmacy and in GP surgeries and its provision was covered editorially in the Cheadle & Tean Times, the local newspaper. GP practices encountering patients who had been referred back by the community pharmacy were provided with a referral form that included an assessment of the urgency with which the pharmacist felt the patient needed to be seen, although the decision for how quickly a patient needed to be seen remained at the practice’s discretion. In the event of a CRP concentration greater than 20mg/L, the patient received a printed copy of their test report to present to their GP.

Patient access and eligibility

There were three ways that patients could access the scheme: presentation at a GP practice, referral by the pharmacy and self-referral. In all cases, the decision to carry out a POC CRP test remained with the pharmacist. The first consultation of a current episode of acute cough of duration <4 weeks that was considered to be caused by a lower RTI (LRTI) provided eligibility into the scheme. Furthermore, at the time of the consultation, at least one of the following four symptoms was necessary: shortness of breath, wheezing, chest pain or auscultation abnormalities. Also, at least one of the following five symptoms was necessary: fever according patient history or measurement >38ºC, perspiring, headache, myalgia or feeling generally unwell.

Patients were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: patients who have been experiencing symptoms for less than three days (72 hours), patients who have been experiencing symptoms for three weeks or more, or patients suffering from chronic inflammatory conditions (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis). Children and pregnant or breastfeeding women were also excluded because of NICE guidance. Furthermore, there is some evidence that CRP levels are elevated during pregnancy and while breastfeeding, and the use of a lancet deemed it suitable to exclude children as this could have caused pain.

Patients presenting with severe symptoms or any symptoms of concern were referred immediately to the appropriate healthcare professional.

Consultation

The first conversation with the patient, prior to any discussion about the service, was performed by the medicine counter assistant and included the Who, What, How, Action, Medication taken (WWHAM) questions[21]

. The WWHAM was also used to identify how long the patient had experienced symptoms for. If this was found to be greater than three days, the patient was referred to the pharmacist to potentially undertake a POC CRP test. The pharmacist asked the patient questions to establish if they should proceed with the service or if they required referral to another healthcare professional. There were general ‘red flag’ signs and symptoms that always needed referral (e.g. symptoms lasting for three weeks or more, rash, muffled voice, noisy breathing, high-pitched sound during breathing, difficulty breathing, difficulty swallowing, unable to swallow enough fluids, signs of blood in sputum, symptoms of any other infection or serious illness, or the patient had already taken antibiotics for this RTI).

Data collection

During the consultation, the pharmacist took written consent and noted the patient’s inclusion criteria[20]

. After general questions, patients were asked to participate in a simple symptom score self-assessment, with responses to statements ranging from 0 (no symptoms) to 5 (severe symptoms). All patients were followed up at three days and seven days by telephone by the pharmacist to assess their course of action following the pharmacist intervention and their satisfaction with the process (the list of follow-up questions are provided in Box 1). Responses were recorded on PharmOutcomes®, a web-based system that helps community pharmacies provide services more effectively and makes it easier for commissioners to audit and manage these services. By collating information on pharmacy services, it enables local and national level analysis and reporting on the effectiveness of commissioned services, helping to improve the evidence base for community pharmacy services.

Box 1: Follow-up questions for patients used in the telephone interview on days 3 and 7

Day 3 questions only:

- Were you expecting the test? (yes/no)

- Did the test help your understanding? (yes/no)

- Was it painful? (yes/no)

- Were the results easy to understand? (yes/no)

- Would you have otherwise have visited the GP? (yes/no)

- Would you have otherwise have visited another healthcare professional? (yes/no)

- Would you have expected antibiotics? (yes/no)

- Can I call back in 4 days? (yes/no)

Day 3 and 7 questions:

- On a scale of 1–5 how would you assess the following symptoms:

- Shortness of breath (likert scale 1–5)

- Wheezing (likert scale 1–5)

- Chest pain (likert scale 1–5)

- Breathing abnormalities (likert scale 1–5)

- Perspiring (likert scale 1–5)

- Headache (likert scale 1–5)

- Myalgia (likert scale 1–5)

- Feeling generally unwell (likert scale 1–5)

- Others (please state)

- Do you have a fever (>38°C)? (yes/no)

- Have you subsequently needed to visit a GP or another healthcare professional as a result of these symptoms? (yes/no)

- If yes, did you receive an antibiotic prescription? (yes/no)

Self-care advice for those patients not requiring the POC CRP test

Patients were advised that RTIs are generally self-limiting, with most people recovering after a week with or without antibiotics. Over-the-counter treatments were recommended to relieve the symptoms of a RTI. Other advice included: drinking plenty of fluids, the possible use of steam inhalation and vapour rubs, sore throat lozenges, warm drinks with honey and lemon, salt (saline) nasal drops, and the use of licensed herbal remedies (e.g. echinacea and pelargonium extracts).

Results

Patient demographics

This pilot study was performed over six months between mid-February and mid-August 2017. A total of 52 patients were entered into the study. In total, 25 patients were referred via GP surgeries, 6 by pharmacy staff and 21 self-referred as a result of the local awareness campaign. Patients were aged 16–75 years, with 88% aged over 40 years.

Initial consultation and POC CRP testing

Table 2 summarises the simple symptom score patient self-assessments at the point of entry into the study.

| Symptom | Self-assessment score | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Absent | Present | |

| Dyspnoea | 21 | 2 | 6 | 13 | 7 | 3 | – | – |

| Wheeze | 20 | 1 | 11 | 15 | 5 | 0 | – | – |

| Chest pain | 44 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 1 | – | – |

| Perspiration | 25 | 2 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 4 | – | – |

| Headache | 29 | 2 | 4 | 10 | 6 | 1 | – | – |

| Myalgia | 27 | 0 | 4 | 13 | 2 | 6 | – | – |

| Unwell | 6 | 2 | 11 | 15 | 9 | 9 | – | – |

| Fever >38°C | – | – | – | – | – | – | 39 | 13 |

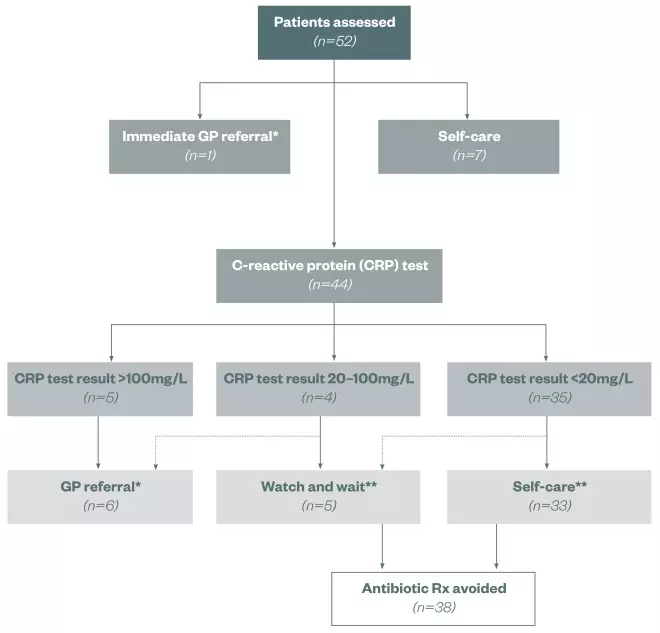

Of the 52 patients, 7 were recommended self care, 1 was immediately referred to their GP practice, and 44 were considered suitable for POC CRP testing.

Of the 44 patients who received a POC CRP test, 5 patients were found to have levels of CRP greater than 100mg/L, 4 had levels of 20–100mg/L and 35 had levels of less than 20mg/L. Following these assessments and using the guidelines in Table 1, 6 patients were referred directly to the GP surgery, 5 were allocated to a ‘watch and wait’ category and 33 were recommended self-care treatment. All patients understood the purpose of the test once it had been explained to them. No patients experienced pain and they all found the results easy to understand.

Follow-up call

Telephone follow-up with patients (n=44) after 3 and 7 days following entry into the study revealed that all patients reported a satisfactory experience with the quality of the consultation process and intervention. In total, 95% of patients who received the POC CRP test reported that they would have otherwise visited the GP and would have expected to be prescribed antibiotics. Furthermore, of the ‘watch and wait’ and self-care patients (n=38), none had subsequently revisited the pharmacy or sought an appointment at their GP surgery. These events are summarised in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Outcomes of patients entering the trial

*Subsequent antibiotic Rx **No subsequent GP referral

The trial was performed between February and August 2017 in a rural community pharmacy in North Staffordshire, UK

Discussion

This pilot study is believed to be the first in the UK to deliver POC CRP testing in community pharmacy after undertaking skills training with pharmacy staff regarding the test and its interpretation. A low CRP test result, which was expected to occur in the majority of patients with RTIs, was found to be reassuring for the patient, confirming that the illness is mild and most probably self-limiting. In addition, very high test results helped provide staff with confidence in their recommendation for patients to visit a GP and seek consideration of antibiotic treatment. To achieve this, GPs had to be aware of the usefulness of the test and had to be able to properly interpret the results. These are crucial conditions for a positive effect of the CRP intervention. The pragmatic nature of the study, which leaves treatment decisions up to the responsible pharmacists, enhances the applicability and generalisability of the findings.

Although the numbers of participants in the study were relatively small, mainly owing to the season within which it was performed, it indicates that pharmacies and GP surgeries can work together to enable community pharmacy to deliver an efficient service that has a high degree of patient satisfaction. It also demonstrates the potential to significantly diminish the burden caused by RTIs in general practice; of the 44 patients receiving the POC test, 38 (86%) did not require referral to their GP or an antibiotic prescription. However, owing to the lack of access to the prescription data from the surgeries, it was not possible to compare if there was a reduction in the number of prescription items during the study (February–August 2017) versus the same time period the year before (February–August 2016).

If these interventions decrease antibiotic prescribing and enhance patient satisfaction with favourable clinical outcomes, they could be used to enhance the quality of a large number of consultations in primary care. A full cost-effectiveness analysis is needed to evaluate the efficiency of the intervention; this is proposed in a follow-up trial, scheduled for the winter season, which will include a greater number of pharmacies operating in a broader demographic. If these interventions are shown to be effective and cost efficient, they may be refined and used to promote uptake in everyday care.

Financial and conflicts of interest disclosure:

This study was sponsored by Schwabe Pharma UK Ltd, which funded pharmacy service payments and Finecare II analyser hire, and Ciga Healthcare Ltd, which funded Finecare analyser test kits. Michael Wakeman has worked as a consultant for Schwabe Pharma; however, he nor Schwabe Pharma received any financial benefit from this study. The authors, with the exception of David Watwood, an employee of Ciga Healthcare Ltd, have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organisation or entity with a financial interest in, or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript. No writing assistance was utilised in the production of this manuscript.

Reading this article counts towards your CPD

You can use the following forms to record your learning and action points from this article from Pharmaceutical Journal Publications.

Your CPD module results are stored against your account here at The Pharmaceutical Journal. You must be registered and logged into the site to do this. To review your module results, go to the ‘My Account’ tab and then ‘My CPD’.

Any training, learning or development activities that you undertake for CPD can also be recorded as evidence as part of your RPS Faculty practice-based portfolio when preparing for Faculty membership. To start your RPS Faculty journey today, access the portfolio and tools at www.rpharms.com/Faculty

If your learning was planned in advance, please click:

If your learning was spontaneous, please click:

References

[1] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Respiratory tract infections – antibiotic prescribing. Prescribing of antibiotics for self-limiting respiratory tract infections in adults and children in primary care. NICE clinical guideline 69 [CG69]. 2008. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg69 (accessed May 2018)

[2] Smith SM, Fahey T, Smucny J & Becker LA. Antibiotics for acute bronchitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;3:CD000245. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000245.pub3

[3] Spinks A, Glasziou PP & Del Mar CB. Antibiotics for sore throat. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;11:CD000023. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000023.pub4

[4] Thornley T, Marshall G, Howard P & Wilson AP. A feasibility service evaluation of screening and treatment of group A streptococcal pharyngitis in community pharmacies. J Antimicrob Chemother 2016;71(11):3293–3299. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw264

[5] McNulty CA, Nichols T, French DP et al. Expectations for consultations and antibiotics for respiratory tract infection in primary care: The RTI clinical iceberg. BJGP 2013;63(612):e429–e436. doi: 10.3399/bjgp13x669149

[6] McNulty C, Joshi P, Butler CC et al. Have the public’s expectations for antibiotics for acute uncomplicated respiratory tract infections changed since the H1N1 influenza pandemic? A qualitative interview and quantitative questionnaire study. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000674. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000674

[7] Wellcome Trust. Exploring the consumer perspective on antimicrobial resistance. Available at: https://wellcome.ac.uk/sites/default/files/exploring-consumer-perspective-on-antimicrobial-resistance-jun15.pdf (accessed May 2018)

[8] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Pneumonia in adults: diagnosis and management. Clinical guideline [CG191]. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg191 (accessed May 2018)

[9] Public Health England. Management and treatment of common infections. Antibiotic guidance for primary care: for consultation and local adaptation. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/managing-common-infections-guidance-for-primary-care (accessed May 2018)

[10] Woodhead M, Blasi F, Ewig S et al. Guidelines for the management of adult lower respiratory tract infections – full version. Clin Microbiol Infect 2011;17(6):E1–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03672.x

[11] Aabenhus R, Jensen J, Jorgensen K et al. Biomarkers as point-of-care tests to guide prescription of antibiotics in patients with acute respiratory infections in primary care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014:CD010130. doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd010130.pub2

[12] Cals JWL, Ament AJHA, Hood K et al. C-reactive protein point of care testing and physician communication skills training for lower respiratory tract infections in general practice: Economic evaluation of a cluster randomized trial. J Eval Clin Pract 2011;17(6):1059–1069. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01472.x

[13] Oppong R, Jit M, Smith RD et al. Cost-effectiveness of point-of-care C-reactive protein testing to inform antibiotic prescribing decisions. Br J Gen Pract 2013;63(612):e465–e471. doi: 10.3399/bjgp13x669185

[14] Hunter R. Cost-effectiveness of point-of-care C-reactive protein tests for respiratory tract infection in primary care in England. Adv Ther 2015;32(1):69–85. doi: 10.1007/s12325-015-0180-x

[15] Cooke J, Butler C, Hopstaken R et al. Narrative review of primary care point-of-care testing (POCT) and antibacterial use in respiratory tract infection (RTI). BMJ Open Respir Res 2015;2:1–10. doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2015-000086

[16] Cooke J. C-Reactive Protein (CRP) as a point of care test (POCT) to assist in the management of patients presenting with symptoms of respiratory tract infection (RTI) – a new role for Community Pharmacists? Pharm Manag 2016;32:25–29.

[17] Bacci JL, Klepser D, Tilley H et al. Community pharmacy-based point-of-care testing: a case study of pharmacist-physician collaborative working relationships. Res Social Adm Pharm 2018;14(1):112–115. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2016.12.005

[18] Corn CE, Klepser DG, Dering-Anderson AM et al. Observation of a pharmacist-conducted group a streptococcal pharyngitis point-of-care test: a time and motion study. J Pharm Pract 2017:897190017710518. doi: 10.1177/0897190017710518

[19] Hughes A, Gwyn L & Clarke C. Evaluating a point-of-care C-reactive protein test to support antibiotic prescribing decisions in a general practice. Clin Pharm 2016;8(10). doi: 10.1211/CP.2016.20201688

[20] North Staffordshire and Stoke on Trent Local Pharmaceutical Committee (LPC). Point of care testing. Available at: http://www.northstaffslpc.co.uk/point-of-care-testing-for-rti/ (accessed May 2018)

[21] Rutter PM, Horsley E & Brown DT. Evaluation of community pharmacists’ recommendations to standardized patient scenarios. Ann Pharmacother 2004;38:1080–1085. doi: 10.1345/aph.1d519