DR P. MARAZZI/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY / The Pharmaceutical Journal

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) develops during the early pubertal years and is the most common endocrinopathy (hormonal condition) affecting women of reproductive age[1],[2]

. In the UK, around one in ten women are affected by PCOS[3]

.

Prevalence of the syndrome varies according to diagnostic consensus used, with estimates ranging from 6% (using the National Institutes of Health consensus) to 18% (using the Rotterdam consensus) of reproductive-aged women of different ethinicity[4]

. One systematic review and meta-analysis suggested the incidence of PCOS is lowest in Chinese women (5.6%) and Caucasian women (5.5%), followed by Middle Eastern women (6.1%) and black women (7.4%)[4]

.

Pharmacists can provide advice to patients on how to take medicines to treat the symptoms of PCOS, as well as counsel concerned patients and patients who are trying to conceive. This article describes the management options available, including three worked case studies.

Causes and pathophysiology

The exact aetiology is unknown, but PCOS often runs in families and appears to be the result of environmental and genetic factors[5]

. Other factors thought to affect the pathophysiology and phenotype of PCOS include:

- Insulin secretion/sensitivity;

- Lack of exercise and activity;

- Persistent hormone imbalance[6]

.

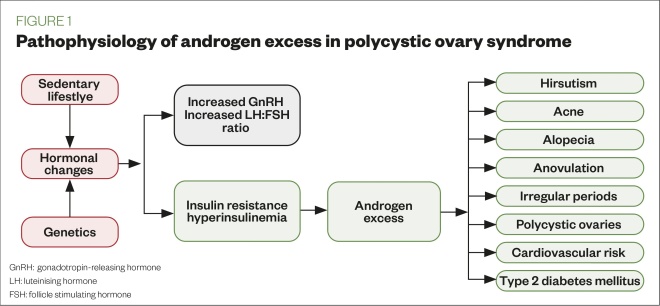

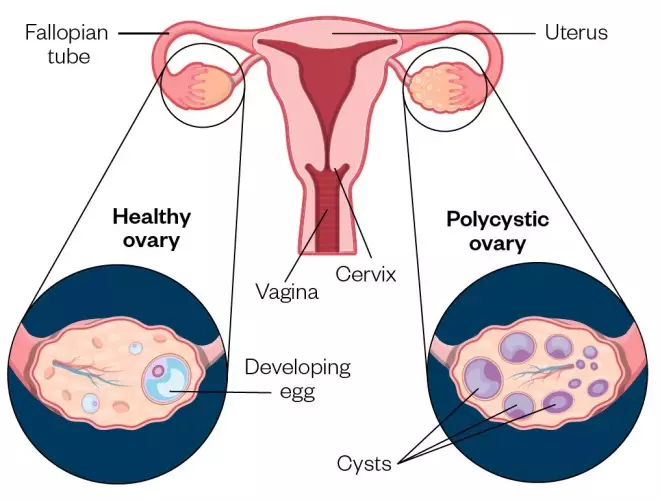

However, not all factors affect all women, resulting in different associated pathologies (see Figure 1). For example, androgen excess can lead to infertility, owing to numerous cysts in the ovaries (see Figure 2), type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and cardiovascular disease[7],[8],[9]

.

Figure 1: Pathophysiology of androgen excess in polycystic ovary syndrome

Source: Mclean

Figure 2: A normal ovary compared with a polycystic ovary. The polycystic ovary has many fluid-filled sacs (follicles) that surround the eggs

Source: Mclean/Shutterstock.com

Symptoms

These typically develop soon after menarche and can vary from woman to woman. They include:

- Menstrual disturbances — oligomenorrhea (infrequent menstruation), amenorrhea (the absence of menstruation) and prolonged erratic menstrual bleeding;

- Obesity — weight gain, being overweight and difficulty losing weight;

- Hirsutism — thick, excessive hair growth on the face, neck and body (see Figure 3);

- Alopecia and/or thinning of hair on the head (see Figure 3);

- Acne as a result of hyperandrogenism;

- Acanthosis nigricans — thick, pigmented skin over the nape of neck, axilla, underarms, inner thigh and groin, which occurs as a result of insulin resistance (see Figure 3)[10],[11],[12],[13]

.

Figure 3: Symptoms commonly seen in polycystic ovary syndrome: (a) hirsutism; (b) thinning hair/alopecia and (c) acanthosis nigricans

Source: Science Photo Library/Shutterstock.com

The symptoms of PCOS can affect self-esteem; therefore, women with PCOS may also have mental health conditions, such as low mood, anxiety and depression[14]

.

Diagnosis

There are no standardised diagnostic criteria to identify PCOS, but it can be diagnosed if two of the following three criteria are met, provided all other causes of menstrual disturbance and hyperandrogenism are excluded[15]

:

- Infrequent or no menstruation;

- Hyperandrogenism (i.e. acne, hirsutism);

- Polycystic ovarian morphology (as seen on an ultrasound scan)[16]

.

Physical appearance, blood pressure checks, weight control and blood tests are commonly assessed in initial appointments to confirm if the patient can be referred for an ultrasound scan.

Before receiving a PCOS diagnosis, women may have visited their community pharmacist for reasons relating to the condition (e.g. advice regarding acne), while some may have continually visited their GP until obtaining a referral to a gynaecologist. Therefore, diagnosis can be a lengthy and distressing time for the patient.

Complications

PCOS is the underlying cause in 75% of women with infertility owing to anovulation[16]

. Although women with PCOS may conceive, they are more at risk of pregnancy complications (e.g. preeclampsia, hypertension) than women without PCOS[16]

. Women with PCOS who are planning a pregnancy should be offered a 75g oral glucose tolerance test. This test should be repeated at 24–28 weeks gestation[16]

. Women with PCOS who experience fertility problems should be referred to a specialist[17]

.

Owing to the abnormal hormone levels observed in PCOS, metabolic disease (i.e. glucose intolerance, T2DM or dyslipidaemia) and an increased cardiovascular risk are more common in women with the condition[18],[19]

. Women with PCOS are also three times more likely to develop endometrial cancer compared with women without PCOS[16]

.

Management

Lifestyle changes

The first-line management options for PCOS include regular exercise (e.g. 150 minutes of brisk walking per week), good hydration, weight control and following a healthy eating plan (e.g. high protein, low carbohydrate and low glycaemic load diets) to aid weight loss and improve insulin sensitivity[20],[21]

. Research has shown that weight loss of 5–10% of initial body weight in women who are obese can significantly improve symptoms of PCOS and may improve the chance of pregnancy[21]

.

Pharmacological management

Combined oral contraceptives

A combined oral contraceptive (COC) pill can be prescribed to help:

- Control androgen excess (excess hair growth, acne);

- Regulate periods and painful periods.

COCs are contraindicated in patients with risk factors, such as venous thromboembolism. Treatment effectiveness should be assessed after a minimum of six months[16]

.

Common side effects tend to disappear after treatment has become established; however, it is common for patients to experience breast tenderness, bloating, altered mood and weight increase[22]

. Patients experiencing these symptoms should be assessed by a specialist.

Medroxyprogesterone

For women with infrequent or no menstruation, medroxyprogesterone can be prescribed at 10mg for 14 days to induce bleeding, with a follow-up ultrasound undertaken to assess for endometrial thickening. Depending on the result of the ultrasound, patients may be continued on medroxyprogesterone 10mg for 14 days or started on the COC or hormonal coil with levonorgestrel. Women with PCOS who are amenorrhoeic are not oestrogen deficient and do not need osteoporosis prophylaxis when taking medroxyprogesterone[16]

.

Clomifene

For women with ovulatory dysfunction who are trying to conceive, specialists may prescribe clomifene 50mg once-daily. The treatment is for five days starting on day five of the menstrual cycle; although, if the patient has not had recent uterine bleeding, it may be started at any time. If ovulation has not occurred after the first course of therapy, a second course of clomifene 100mg once-daily for five days can be prescribed. The summary of product characteristics (SmPC) contraindicates clomifene in patients with liver disease, abnormal uterine bleeding and ovarian cysts (except those owing to PCOS)[23]

. Long-term cyclical therapy, defined as beyond a total of six cycles, is not recommended[23]

.

Adverse effects appear to be dose-related, occurring more frequently at a higher dose. Ovarian enlargement, hot flushes, abdominal-pelvic discomfort, nausea and vomiting, breast discomfort, visual symptoms, headache and intermenstrual spotting have been commonly reported in the SmPC[23]

.

Metformin

Although metformin is only licensed in T2DM, specialists may use it unlicensed in adolescents with PCOS to palliate symptoms and in clomifene-resistant patients who decide to opt for in vitro fertilisation.

In PCOS, long-term metformin treatment may increase ovulation, improve menstrual cyclicity and reduce serum androgen levels, as well as decrease the risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome[24],[25]

. The dose has not been fully established and varies between 1g and 2g per day, and there is no standard duration of treatment. Furthermore, metformin is contraindicated in patients with renal or hepatic insufficiency. Side effects include gastrointestinal disorders and taste disturbance[26]

.

Excess hair growth and acne

These symptoms can be managed with the COC pill, topical creams/gels and laser hair removal. Spironolactone is used as an unlicensed product for acne vulgaris owing to its antiandrogen-acting properties[27],[28]

. Other antiandrogens, such as finasteride and flutamide, can be used for hirsutism[29]

. Unlicensed treatments are prescribed by dermatologists and require close monitoring of efficacy and side effects; therefore, these should be reserved as a last option.

Case studies

Case study 1: a teenager with suspected polycystic ovary syndrome*

A regular patient comes to the pharmacy with her daughter, Nadia, who is aged 12 years and is experiencing long and painful periods, as well as mild acne.

Advice and recommendations

Nadia should be advised to record the regularity and duration of her periods, as well as a description of the pain (i.e. duration and intensity). If she feels more tired than normal, this could possibly indicate anaemia.

Explain that mild acne is normal owing to hormonal changes, but it is important to follow a healthy lifestyle (i.e. maintain a balanced diet, keep hydrated and exercise regularly), as well as avoiding picking spots to help maintain good skincare.

Advise Nadia’s mother to give her 500mg of paracetamol up to four times daily and ibuprofen 200–400mg, as recommended in the summary of product characteristics, to control the pain during her period. However, if both analgesics are taken and symptoms persist, she should visit the GP for further assessment.

Diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) in adolescents should include a thorough family history, exclusion of other causes of hyperandrogenism (e.g. Cushing’s syndrome) and appropriate laboratory tests. The scarcity of controlled clinical trials makes pharmacological management of PCOS in this patient group difficult. Therapeutic options include lifestyle intervention, oral contraceptive pills and insulin sensitisers. Long-term follow-up is also needed to determine the effectiveness of these approaches in changing the natural history of the reproductive and metabolic outcomes, without causing undue harm[30]

.

Case study 2: a woman with polycystic ovary syndrome who is trying to conceive*

Sheila is a 35-year-old patient who would like advice about natural remedies to aid conception. She stopped taking the contraceptive pill a year ago, which had been prescribed to control symptoms of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). However, the symptoms, which included weight gain, have come back and she has gained more weight owing to her anxiety. She has been referred to a fertility clinic, but her appointment is in four months. Sheila does not drink alcohol and is not taking any medicines, but she does smoke occasionally.

Advice and recommendations

Listen Sheila’s concerns and provide advice where possible. For example, reassure her that losing weight can increase fertility. Explain that one of the requirements for patients to be eligible to commence assisted reproduction is to have a body mass index of 19–30; being outside of this range is likely to reduce the success of assisted reproduction procedures[17]

. Weight loss can be achieved by following a healthy diet and increasing amount of exercise. She should also be referred to smoking cessation services.

Refer Sheila to her GP so they can assess if she requires an oral glucose tolerance test, as well as to evaluate her anxiety[16]

.

Advise her to start taking folic acid 400 micrograms daily or any other vitamin supplement that contains this in order to prepare the body during pre-conception, as well as other pre-pregnancy advice such as ensuring her vaccinations are up-to-date[31]

.

Furthermore, signpost the patient to support groups for women with PCOS, such as PCOS Challenge and Verity.

Case study 3: a woman with polycystic ovary syndrome who would like information about managing symptoms*

Johanna, aged 25 years, comes to the pharmacy asking for information about how to manage the hair growth and acne on her face.

Johanna explains that she has polycystic ovary syndrome and started taking the combined oral contraceptive pill three months ago. She is worried that although the treatment has helped with most of her symptoms (e.g. her periods are more regular and less painful), the acne on her face and the hair on her chin are still present. The patient confirms there is no family history of cardiovascular disease and she has recently joined a running club to help her maintain a fit and healthy lifestyle.

Advice and recommendations

Since Johanna has only been taking the pill for three months and has seen an improvement in her symptoms, she does not need to go to her GP for referral to a dermatologist. To see the full benefit of the pill, up to six months of treatment is needed; therefore, Johanna should be reassured that it might take another three months for the full effects of treatment to be achieved. She should also be advised to maintain a balanced diet and continue with her running club.

The patient can be advised to buy over-the-counter benzoyl peroxide as a 5% gel or as a 10% wash for her acne. For better efficacy, she should apply it to her face using a cleanser and sun protection moisturiser rather than applying to individual lesions. The treatment can be completed for six weeks and be assessed thereafter[32]

. Johanna should also be advised that non-comedogenic make up is available.

If after six months of treatment, Johanna still has acne and facial hair, she should be referred to her GP for a prescription for topical agents for acne, such as retinoids/antibiotics, or a topical cream for facial hirsutism. However, it is important to advise her that a common side effect of facial hirsutism cream is acne; therefore, hair removal may be a good option for this patient[33]

. Laser removal of facial hair may be available on the NHS in some parts of the UK[34]

.

*All case studies are fictional

About the author

Veronica Chorro-Mari is specialist pharmacist for women and children services, Barts Health NHS Trust, UK

How to have effective consultations on contraception in pharmacy

What benefits do long-acting reversible contraceptives offer compared with other available methods?

Community pharmacists can use this summary of the available devices to address misconceptions & provide effective counselling.

Content supported by Bayer

References

[1] Apter D, Bützow T, Laughlin GA & Yen SS. Accelerated 24-hour luteinizing hormone pulsatile activity in adolescent girls with ovarian hyperandrogenism: relevance to the developmental phase of polycystic ovarian syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1994;79(1):119–125. doi: 10.1210/jcem.79.1.8027216

[2] Conway G, Dewaily D, Diamanti-Kandarakis E et al. The polycystic ovary syndrome: a position statement from the European Society of Endocrinology. Eur J Endocrinol 2014;171(4):1–29. doi: 10.1530/EJE-14-025

[3] March WA, Moore VM, Willson KJ et al. The prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome in a community sample assessed under contrasting diagnostic criteria. Hum Reprod 2010;25(2):544–551. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep399

[4] Ding T, Hardiman PJ, Petersen I et al. The prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome in reproductive-aged women of different ethnicity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget 2017;8(56):96351–96358. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.19180

[5] Barthelmess E & Naz RK. Polycystic ovary syndrome: current status and future perspective. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2014;6:104–119. PMID: 24389146

[6] Joshi M. Polycystic ovary syndrome. International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research 2014;5(12):514–521.

[7] Ajmal N, Khan SZ & Shaikh R. Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and genetic predisposition: a review article. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol X 2019;3:100060. doi: 100060/j.eurox.2019.10.1016

[8] Legro RS. Type 2 diabetes and polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril 2006;86(Supp 1):S16–S17. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.04.010

[9] Dokras A. Cardiovascular disease risk in women with PCOS. Steroids 2013;78(8):773–776. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2013.04.009

[10] Farquhar C. Introduction and history of polycystic ovary syndrome. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2007.

[11] Lim SS, Davies MJ, Norman RJ & Moran LJ. Overweight, obesity and central obesity in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Human Reproduction Update 2012;18(6):618–637. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dms030

[12] Rosenfield RL & Lucky AW. Acne, hirsutism and alopecia in adolescent girls: clinical expressions of androgen excess. Endocrinology and metabolism clinics in North America 1993;22(3):507–532. doi: 10.1016/S0889-8529(18)30148-8

[13] Kumarendran B, O’Reilly MW, Manolopoulos KN et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome, androgen excess, and the risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in women: a longitudinal study based on a United Kingdom primary care database. PLoS 2018;15(3):e1002542. doi: 10.1371/j.eurox. 1002542

[14] Kerchner A, Lester W, Stuart SP et al. Risk of depression and other mental health disorders in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a longitudinal study. Fertil Steril 2009;91(1):207–212. doi: 101016/j.fertnstert.2007.11.022

[15] Dewailly D. Diagnostic criteria for PCOS: is there a need for a rethink? Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2016;37:5–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2016.03.009

[16] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Polycystic ovary syndrome. Clinical Knowledge Summary. 2018. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/polycystic-ovary-syndrome (accessed March 2020)

[17] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Fertility problems: assessment and treatment. Clinical guideline [CG156]. 2017. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg156 (accessed March 2020)

[18] Wang ET, Calderon-Margalit R, Cedars MI et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome and risk for long-term diabetes and dyslipidemia. Obstet Gynaecol 2011;117(1):6–13. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31820209bb

[19] Peigne M & Dewailly D. Long term complications of polycystic ovary syndrome. Ann Endocrinol 2014;75(4):194–199. doi: 10.1016/j.ando.2014.07.111

[20] NHS. Exercise. 2019. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/exercise/#what-counts-as-moderate-aerobic-activity/ (accessed March 2020)

[21] Teede H, Deeks A & Moran L. Polycystic ovary syndrome: a complex condition with psychological, reproductive and metabolic manifestations that impacts on health across the lifespan. BMC Med 2010;8:41. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-41

[22] Electronic medicines compendium. Yasmin®, Microgynon 30®, Mycrogynon 30ED®. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/1607 (accessed March 2020)

[23] Electronic medicines compendium. Clomid 50mg tablets. 2019. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/961/smpc (accessed March 2020)

[24] Nestler JE. Metformin for the treatment of the polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med 2008;358(1):47–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct0707092

[25] Tso L O, Costello MF, Albuquerque LE et al. Metformin treatment before and during IVF or ICSI in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;18(11):CD006105. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006105.pub3

[26] Electronic medicines compendium. Competact 15mg/850mg film-coated tablets. 2018. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/236/smpc (accessed March 2020)

[27] Kim GK & Del Rosso JQ. Oral spironolactone in post-teenage female patients with acne vulgaris: practical considerations for the clinician based on current data and clinical experience. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2012;5(3):37–50. PMID: 22468178

[28] Charny JW, Choi JK & James WD. Spironolactone for the treatment of acne in women, a retrospective study of 110 patients. Int J Womens Dermatol 2017;3(2):111–115. doi: 10.1016/j/ijwd.2016.12.002

[29] Moghetti P, Tosi F, Tosti Aet al. Comparison of spironolactone, flutamide, and finasteride efficacy in the treatment of hirsutism: a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled trial.J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000;85(1):89–94. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.1.6245

[30] Warren-Ulanch J & Arslanian S. Treatment of PCOS in adolescence. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006;20(2):311–330. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2006.02.002

[31] NHS. Trying to get pregnant. 2018. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/pregnancy-and-baby/getting-pregnant/ (accessed March 2020)

[32] Tucker R. Case-based learning; acne vulgaris. Pharm J 2019;302(7926):359–363. doi: 10.1211/PJ.2019.20206226

[33] Electronic medicines compendium. Vaniqa®. 2017. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc (accessed March 2020)

[34] NHS. Polycystic ovary syndrome. 2019. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/polycystic-ovary-syndrome-pcos/ (accessed March 2020)